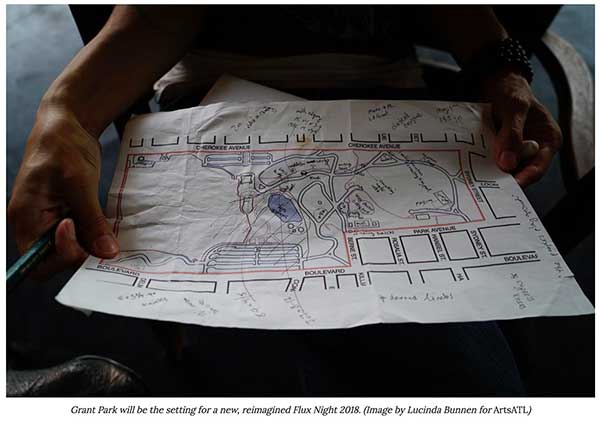

Four women artists prepare a new vision for Flux Night in Grant Park

KENNESAW, Ga. | Sep 24, 2018

This weekend, four artists — all Atlanta-based women — will unveil a new vision for one of the city’s most popular art events, Flux Night. Rachel K. Garceau, Rebecca M.K. Makus, Iman Person and Lauri Stallings (along with their respective collaborators) will present four large-scale public works in Atlanta’s Grant Park for Flux 2018, which for the first time takes place across an entire weekend, September 27–30.

“It’s a way of surveying our environment and its various emotions and needs with this very powerful feminine presence in a very masculine environment,” says Stallings of her work in process. “Our bodies work this way, our bodies have something to say, through no muscular force, just the force of empathy.”

Flux Night debuted in 2010 as a free, one-night exhibition of public art in Castleberry Hill. The combination of engaging contemporary works and an art-filled outdoor environment proved enormously popular, and the annual event grew faster and larger than Flux Projects, the small nonprofit that produces it, could reasonably manage. The event went on hiatus in 2014 and again in 2016 and 2017 as the organization considered new approaches.

The new Flux will extend over four days with special focus times on each day, and the event will culminate on Saturday night with a participatory, light-based happening. Although Flux Projects previously sought to bring in public artists from outside the city for the event, this year, all the artists are Atlanta-based.

The placement of the reimagined event in Grant Park is significant, says Flux Projects executive director Anne Archer Dennington, with this year marking the 135th anniversary of Atlanta’s oldest city park. “When we announced the artists for Flux 2018, I was still looking for a fifth one,” she says, “but along the way I came to realize that the park is the fifth creator in this work.”

Each of the artists will situate the content and form of her work in relation to the history of the site. In 1883, Lemuel Grant, a businessman who owned over 600 acres in Atlanta, gave the city the land for the park because he wanted residents to have a place of refuge where they could experience nature close to the city. Designed by the Olmstead Brothers (the sons of Frederick Law Olmstead, who designed Piedmont Park), the park originally had a lake, which was drained for the zoo expansion; its creeks and runoffs have since disappeared. Across its long history, parts of the park have been neglected. The Grant Park Conservancy, founded in 1996, seeks to rectify problems. Construction and environmental planning projects are currently underway in the ever-evolving urban space.

Iman Person’s Waterlust will trace and recreate the lost waterways of the park with iridescent flowing fabric hovering over the ground. Originally there were five springs in the park, with only one now remaining. “For me, water holds qualities that move beyond the material,” says Person, an artist who has worked across drawing, installation and performance. “It is an activator, a soother of energies and also a conduit for the subconscious. The little water left acts as a thin veil between Atlanta’s past and also its deciding future.” The installation will have three totems that emit sounds of nature. As a viewer follows the banners that stretch and flow across the park, the new path will simultaneously reintroduce the landscape and remind participants of the site’s history.

Following and moving are also central to the work of Rachel K. Garceau, a ceramic artist who works in porcelain. Garceau’s installation Passage will be a labyrinth set in the landscape with a series of handmade slip-cast porcelain stones. Participants will be invited to carry pebble-like sculptures made by dozens of other artists on their journey. “Working with porcelain requires a certain sensitivity and tenderness,” she says. “Placing this fragile work in a public space is an exercise in trust and also an invitation for visitors to reconsider places and objects in a new light. It also speaks to the delicate nature of the park itself and of the flora and fauna who call this place home.”

Movement, strength and fragility are also aspects of Lauri Stallings’ performance work, Land Trees and Women. Viewers will be able to experience the work from sunrise to twilight as Stallings’ group of eight female movement artists, glo, will “move, lean, swarm and push” to convey the natural topography of the land. As viewers follow these artists on their migrations, Stallings says, light will change, weather shift and movements bend. For the first time, Stallings’ work will incorporate four modular sculptures. “Encounter of the audience is unregulated,” says Stallings. “Social performance belongs to a place and a people, relying on the transference from one body to another, a symbol of sorts, a lost democracy. I don’t expect people to follow us for hours. I recognize the endurance ritual here. We touched each other for a moment.”

Rebecca M.K. Makus and her collaborators Peter Torpey and Elly Jessop Nattinger will be building a series of events titled Toolbox. Each day, the team will enter the park with a wheelbarrow filled with a toolbox and simple materials such as batteries, LEDs, clear tape, water, string and a clock. They will select a location, start the timer on the clock and create a temporary performance/installation that they will also document. The works are “sympathetic interventions into the landscape,” Markus says. “The park has a really loud voice,” she explains. “We are transforming echoes of that voice into materiality. Our installations mold themselves to the skin of the park highlighting how the history of the park is written on its body.”

Describing the way artists respond to the natural world, Cézanne once said, “Painting from nature is not copying the object; it is realizing one’s sensations.” The artists of Flux similarly aim to make visitors see how Grant Park is integral to the history, landscape and life of the city as they overlay the natural landscape, intersect with it and respond to it. As Stallings says: “The nature space is where I belong.” As the artists embrace Grant Park, viewers also may encounter a new vision of a place where they belong.

Deanna Sirlin

Related Posts

KSU's Geer College of the Arts Welcomes Shadow Girls Cult's Unraveling for Residency and Performances

KSU Hosts National Storytelling Conference with Headline Performance by the Home Team

Kennesaw State University's Geer College of the Arts Launches Inspiring 2025-26 Season KENNESAW, Ga. | Jul 15, 2025

Bailey School of Music Celebrates Two Student Ensembles Invited to Perform at Georgia's Chapter of the National Music Educators Association