KENNESAW, Ga. | Jun 8, 2022

In November, knee-deep in chilly water, Kennesaw State University graduate students Makayla Ferrari and Jordyn Upton waded into a culvert underneath Interstate 75 near Forsyth, Ga., carrying paper bags, a step ladder and a flashlight.

As traffic rumbled overhead, they stopped under a crack in the concrete ceiling and shined the light, pausing at the sight of a few small, furry bodies seemingly stuck in the tight space.

“There they are,” Ferrari said, setting up the ladder.

Ferrari climbed the ladder carefully, reached up into the crack and then gingerly extracted tricolored bats one by one with a gloved hand. She placed a bat into a protective sack and handed it to Upton, who noted each bat with a Sharpie marker on the outside of the bags.

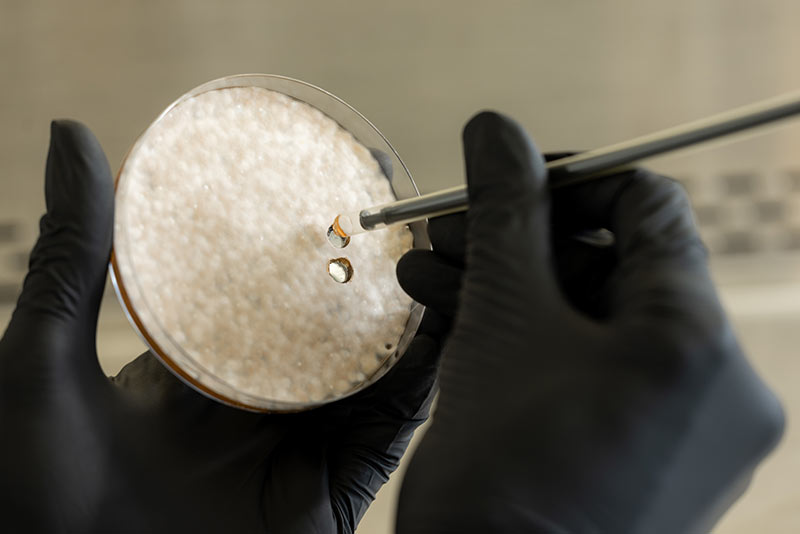

Steps away from the culvert with tools brought from the lab, they would weigh and measure each bat, take fur samples, evaluate the condition of their wings, and take a few other measurements as well. But their most important mission is to look at the bats’ exposed skin, primarily their muzzles, feet and wings for any trace of a white substance that has proven deadly for these nocturnal creatures.

Pseudogymnoascus destructans is the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome (WNS),

a disease that has killed tens of millions of bats in the past decade. The fungus

takes hold while the bats hibernate during the winter, killing them slowly.

“This is a continent-wide problem,” Ferrari said. “This work is important, and it’s amazing that our lab gets to be a part of finding a solution to this disease.”

Kennesaw State’s BioInnovation Laboratory stands at the forefront of research into WNS. Headed up by associate professor Chris Cornelison and postdoctoral researcher Kyle Gabriel and housed within the College of Science and Mathematics, the scientists focus primarily on the fungus and employ both graduate and undergraduate students in their efforts.

While the lab’s portfolio also includes research into mushroom cultivation and additional emerging fungal pathogens, none of those has attracted the same level of attention and funding of the research into WNS, a problem Cornelison has described as “catastrophic.” They have partnerships with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The DNR holds permits allowing the researchers to conduct surveys at multiple sites around the state under their guidance.

Since founding the lab in 2017, Cornelison and Gabriel have received nearly three-quarters of a million dollars in funding for their work on WNS. The most recent is a $90,000 grant from the Bats for the Future Fund that will go toward the construction of an artificial hibernaculum in Rabun County, Ga., to simulate the caves and culverts where bats hibernate, in order to better investigate the efficacy of the treatment methods they’ve developed to mitigate the deadly fungus.

“Bats provide a number of ecological benefits. One of these is eating large amounts of insects, including many crop pests,” Gabriel said. “Thanks to bats, we can reduce the amount of toxic pesticides being applied to crops and the environment. Bats fill a unique niche and provide a significant economic and ecological benefit, not only to humans but also other wildlife.”

According to the University of Georgia Center for Agribusiness and Economic Development, agriculture is a $70 billion per year industry in the state. Additionally, a 2011 study published in Science Magazine estimated the value of bats to the U.S. agricultural industry to be between $3.7 billion and $5.3 billion per year, which accounts for the reduced cost of pesticides no longer needed due to the insects consumed by bats.

A self-professed conservationist, Cornelison approaches the WNS problem from the viewpoint

of conservation and acknowledging the importance of all species. Bats have inherent

value to the ecosystem, he said.

“Organisms have value based on biodiversity,” he said. “The fact that they exist alone presents value worth maintaining those populations. Biodiversity is the most precious commodity on the planet. If there is a way that we can reduce human-mediated species loss with our expertise, it is incumbent upon us to do that. That’s my personal ethos.”

Gabriel’s expertise takes in many aspects of science, including engineering and invention, as evidenced by the building of the artificial hibernaculum. Cornelison and Gabriel developed chemical formulations to kill the fungus in the environment and on the bats while they hibernate. The formulation combines two commercially available liquids — B23 and decanal — that demonstrate significant inhibition of the WNS fungus while having low toxicity to mammals.

Gabriel modified an industrial aerosolizer that can autonomously spray an extremely fine mist of the formulation in the hibernaculum without disturbing the bats. The aerosolizer is pulled — slowly — into the hibernaculum by an electric winch and pulley system attached to a small boat.

Cornelison’s lifelong love for wildlife led to his interest in bats, and his doctoral project helped him learn about the importance of bats to the ecosystem. He wrote his doctoral dissertation on the fungus that causes WNS and shortly thereafter received his first grant. He also worked as a postdoctoral researcher with the U.S. Forest Service, focusing on the mitigation of WNS. That doesn’t make his job any easier, however.

“It’s very difficult to work in conservation biology because everything is dying and things we try to save species sometimes don’t work,” he said. “But I know why it matters, which makes me even more cognizant to it not working, so I focus even harder on finding solutions.”

Gabriel said the data indicate their efforts might be working. From 2017 to 2022, the bat population at Black Diamond Tunnel in north Georgia roughly doubled to a population of 362 at the latest count in January. As with any aspect of science, the process is ongoing and will take years to claim success.

Cornelison credits the efforts of his fellow researchers at Georgia DNR and the U.S.

Fish and Wildlife Service, and undergraduate and graduate students from throughout

the College of Science and Mathematics, with advancing the study and providing a constant

flow of new energy and perspectives toward solving the problem.

Both Ferrari and Upton are in the Masters of Science in Integrative Biology program with theses focused on bat research. Ferrari’s thesis involves how various types of bat hibernacula affect susceptibility to WNS, while Upton’s thesis involves research into the microbiomes found on bat wings. Upton presented at the National Council on Undergraduate Research hosted by KSU in 2018, where she met Cornelison for the first time and, after discussing her project and learning about the BioInnovation Lab, realized that she belonged in the lab and at Kennesaw State.

“I had mostly done genetic barcoding and population genetics work before, but I was slowly getting more excited by wildlife diseases,” Upton said. “Since the BioInnovation Lab had projects dedicated to studying white-nose syndrome, I figured it was a good fit and came to study under Dr. Cornelison. I never aimed to study bats for a career, but this is where research has taken me and I love it.”

At the culvert last fall, Ferrari and Upton worked with four researchers from Georgia DNR. That day, they processed 15 bats, finding no evidence of WNS. Both Ferrari and Upton held the tiny, flying mammals in their hands, examining them one last time before letting each go. Almost immediately, the bats flew back into the culvert, where they would spend the winter hibernating.

– Dave Shelles

Photos by Jason Getz

Research Matters: What if kids saw music through rose-colored glasses?

New research examines trust in AI as first responders train with robotic teammates

Associate professor leverages Fukushima research to advocate for farmers post-disaster

New research shows emotional triggers drive belief in fake news

A leader in innovative teaching and learning, Kennesaw State University offers undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral degrees to its more than 51,000 students. Kennesaw State is a member of the University System of Georgia with 11 academic colleges. The university's vibrant campus culture, diverse population, strong global ties, and entrepreneurial spirit draw students from throughout the country and the world. Kennesaw State is a Carnegie-designated doctoral research institution (R2), placing it among an elite group of only 8 percent of U.S. colleges and universities with an R1 or R2 status. For more information, visit kennesaw.edu.