KENNESAW, Ga. | Oct 9, 2025

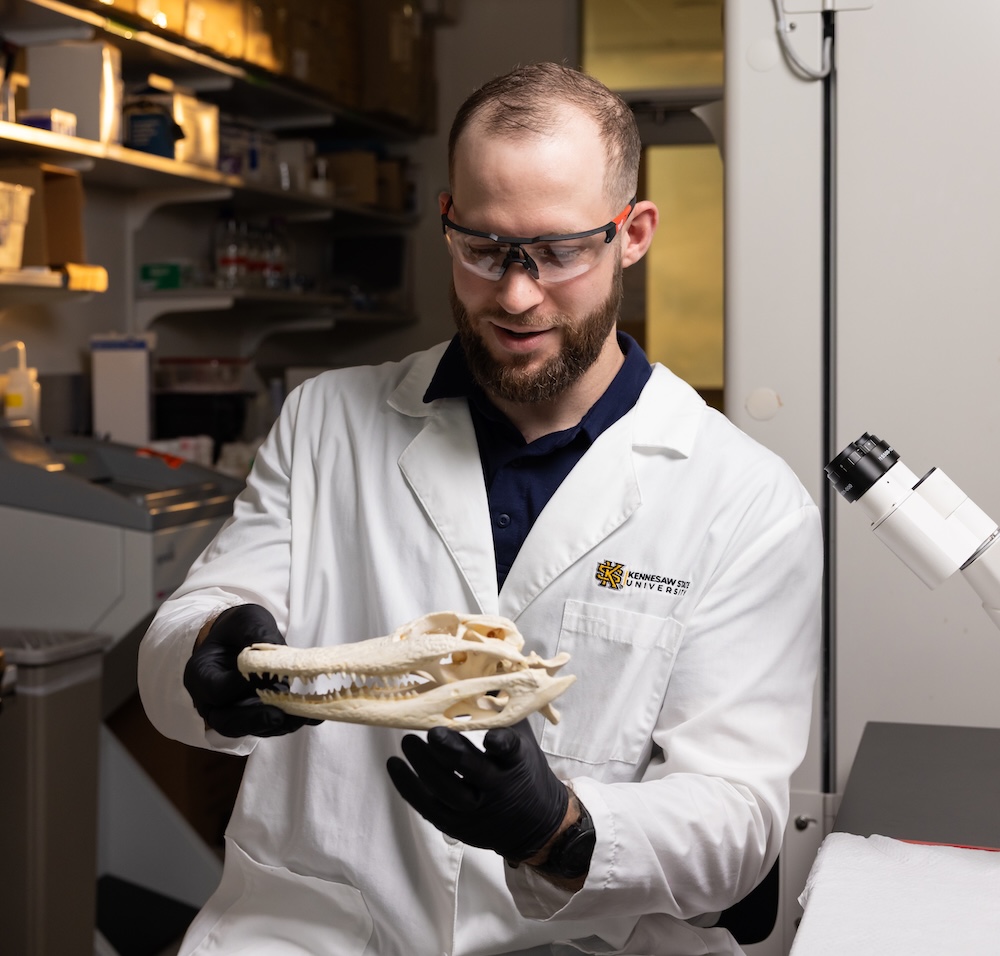

Kennesaw State University graduate student Ben Angalet has gotten up close and personal with dozens of alligators to find the tongue glands that tell a crucial environmental tale about reptiles saltwater and climate change.

“I learned that there’s very little research on this topic, that most of the research on these lingual glands was only done on crocodiles,” he said. “So I figured I’d catch some alligators and see whether populations differ and their abilities to tolerate prolonged saltwater exposure.”

Angalet, a second-year student in KSU’s Master of Science in Integrative Biology program, spent parts of the 2024-25 academic year sampling alligators in four South Georgia locations, including Jekyll Island and the Okefenokee Swamp.

Armed with a large fishing pole, an engineer-designed jaw prop, some collections equipment and his own fearlessness, Angalet searched the tongues of almost 50 alligators for that critical gland, originally discovered in Australian saltwater crocodiles nearly 50 years ago. He is now analyzing his data in anticipation of a spring 2026 thesis defense and graduation.

Angalet earned his bachelor’s degree in biology from the College of Coastal Georgia in Brunswick and immediately went to work as a ranger at Jekyll Island. Originally from Woodstock, he later moved to the Atlanta area and took a job as a laboratory coordinator in KSU’s College of Science and Mathematics.

Combining his work in reptile recovery at Jekyll with an interest in advancing his education, he found his way to the lab of associate professor of biology Nick Green, a biostatistician and ecologist who studies how humans influence wildlife and ecosystems.

“When I started at KSU, I learned about the Tuition Assistance Program, which made it possible for me to take my master’s studies,” Angalet said. “Then I decided I had to find a professor who could work with me, and Dr. Green has a tough time saying no to cool projects. I was able to get him to stray away from his small mammal work for a little bit and help me do my gator stuff.”

Green said he initially balked at the project before agreeing that learning how alligators adjust to changing environments fits right in with his lab’s area of study. Green studies how small mammal communities adjust to urbanization, so it made perfect sense – alligators are yet another animal adapting to human encroachment on habitat.

“A lot of the reason that people might be concerned about how alligators regulate salt in their body has to do with the fact that, as climate warms, the oceans are going to expand,” Green said. “We're seeing sea level rise. More freshwater species will have to adapt to saltwater conditions. Really, this isn't just about alligator tongue glands, it's about how a big apex predator in these coastal and swampy ecosystems adapts to climate change.”

In the pre-experiment literature review, Angalet only found research on crocodiles making the transition between salt- and freshwater environments – very little on alligators. An Australian scientist named Lawrence Taplin conducted the research in the 1970s and 1980s, and Angalet learned of his work over the course of several late-night Zoom calls with Taplin. Angalet said he derived inspiration from those calls.

“What justified me doing this project was that there definitely hasn't been anything going on with it, and I've been following his protocols and practices and his guidance on how to do this on live, wild alligators,” Angalet said. “It can be sketchy sometimes, but it was fun. Everyone's still got their fingers.”

Angalet said the process starts with casting a hook with no barbs from an industrial strength fishing rod into the water, then fighting a thrashing apex predator for anywhere from 15 seconds to several minutes, while reeling it to shore and securing it to a spinal board with ropes. He then entices the alligator to bite down, sticks a large prop into its mouth, taping the mouth to the rods of the prop, and then using a conical cutting device to extract two of the glands from the alligator’s tongue. He said the safety of the animal remained top of mind, though a certain amount of self-preservation takes over, too.

“There's always a big appreciation for each animal,” he said. “We used local anesthetics when we took out any biopsies so they wouldn't feel anything. I'm glad I took videos because the whole time I was just blacked out, just trying to do my work and get everything done. It was hard to appreciate it sometimes, which is why I wanted to get lots of footage and pictures so I can look back on it.”

He admitted the switch to the lab work was difficult after the successful hunts in South Georgia, but he hopes to get back into the wild again. He plans to pursue a doctoral degree, but also is open to staying at Kennesaw State as a staffer or faculty member. He credited Green for giving him a lot of leeway for this project, and said KSU encourages its students consistently in that way.

“Dr. Green told me from the start that this is my project. If I can make it work, then make it work,” Angalet said. “More graduate students should take advantage of those opportunities and really make a master’s what you want it to be. Faculty at KSU are willing to work with you and let you branch out and do things that you are interested in. An experience like this can make you more confident as a scientist, and I think everyone is capable of doing that.”

– Story by Dave Shelles

Photos by Matt Yung

A leader in innovative teaching and learning, Kennesaw State University offers undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral degrees to its more than 51,000 students. Kennesaw State is a member of the University System of Georgia with 11 academic colleges. The university's vibrant campus culture, diverse population, strong global ties, and entrepreneurial spirit draw students from throughout the country and the world. Kennesaw State is a Carnegie-designated doctoral research institution (R2), placing it among an elite group of only 8 percent of U.S. colleges and universities with an R1 or R2 status. For more information, visit kennesaw.edu.